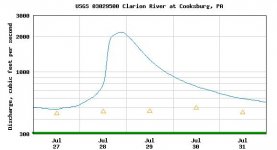

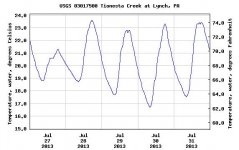

Flow vs. clarity is another issue, and you can use the graphs to guestimate that. Yeah, when you get a spike, you usually get muddy too. But it's not as simple as saying that X cfs = a certain level of clarity. A really big spike clears at a higher cfs, maybe above what a little spike looks like.

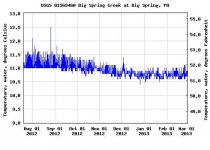

I'll try to show some graph examples I set up for the newbie jam when I get the chance. But look at the end of the spike. Usually you get an area where it's really beginning to level out. It may not be back down at "pre-rain" levels, but where the line is transferring quickly from mostly vertical to mostly horizontal. That's the point where you are transitioning from mostly runoff to mostly groundwater (which may be charged up). So you will be clearing, and temperatures reverting to standard for the stream, etc.

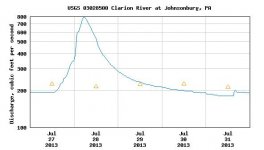

That also tells you what kind of a stream it is. How steady is the groundwater? On a stream with a stable "base" flow like many limestoners, those horizontal areas between rains will be nearly flat. On a freestoner with poor water residency times, even the flat "base flow" areas will be pretty slanted. Probably not the place you want to go if it hasn't rained a drop in 3 weeks.

You can also look at historical data by plugging in dates. Look for clean spikes, meaning rain and done. This tells you how the stream responds to rain. How quickly it rises and falls. And compare dates with upstream and downstream areas. Do it for the same season in question, as it does change a little from summer to winter, etc. In general, bigger streams rise and fall slower, with broader, smoothed peaks. Small streams rise and fall quickly, and are more "spiky".

And the effect is delayed. i.e. a large stream may not even begin to rise much until the day after, by which time it's tribs are already dropping back to normal. You can see by how much.

You can use this in planning ahead. So if you see you're supposed to get 0.50" of rain tomorrow, and your planning a big trip. You can look up several gauges in the watershed, or a nearby one, and look for a similar event in a past year. And thus predict how each stream will respond and plan your trip. i.e., you can say, ok, during the rain I'll fish the big water on day 1, while it's raining, which won't have risen yet, while the little streams will blow out almost immediately. On day 2, that big stream will be rising fast and the medium sized tribs are blown out, but this little trib (and others of it's approximate size) will be just getting back to fishable. Perfect. On day 3, the little one will be on the low side, and the big one still blown out, but the medium ones will be optimal. etc. etc.

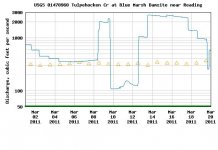

For tailwaters, you can also see how they manage the dam, especially if you have a gauge above and below the dam, and on the next stream down. It's very common that BEFORE an expected rain, they let a lot of water out and lower the pool. When the rain hits, they wait till the incoming water starts spiking, and then start holding back, making the outflow lower. When the water WAY downstream starts dropping, then they increase the flow again.

Knowing what to expect is a key to success in fishing. With some logic, you can get fairly good at predicting. It's still based on logic, not gauges, but the gauges in essence calibrate your predictions.